Revealed: How the No 10 grid strangles effective communication

A government ‘playlist’ of campaigns could cut through more powerfully than an old-style grid of worthy policy nuggets

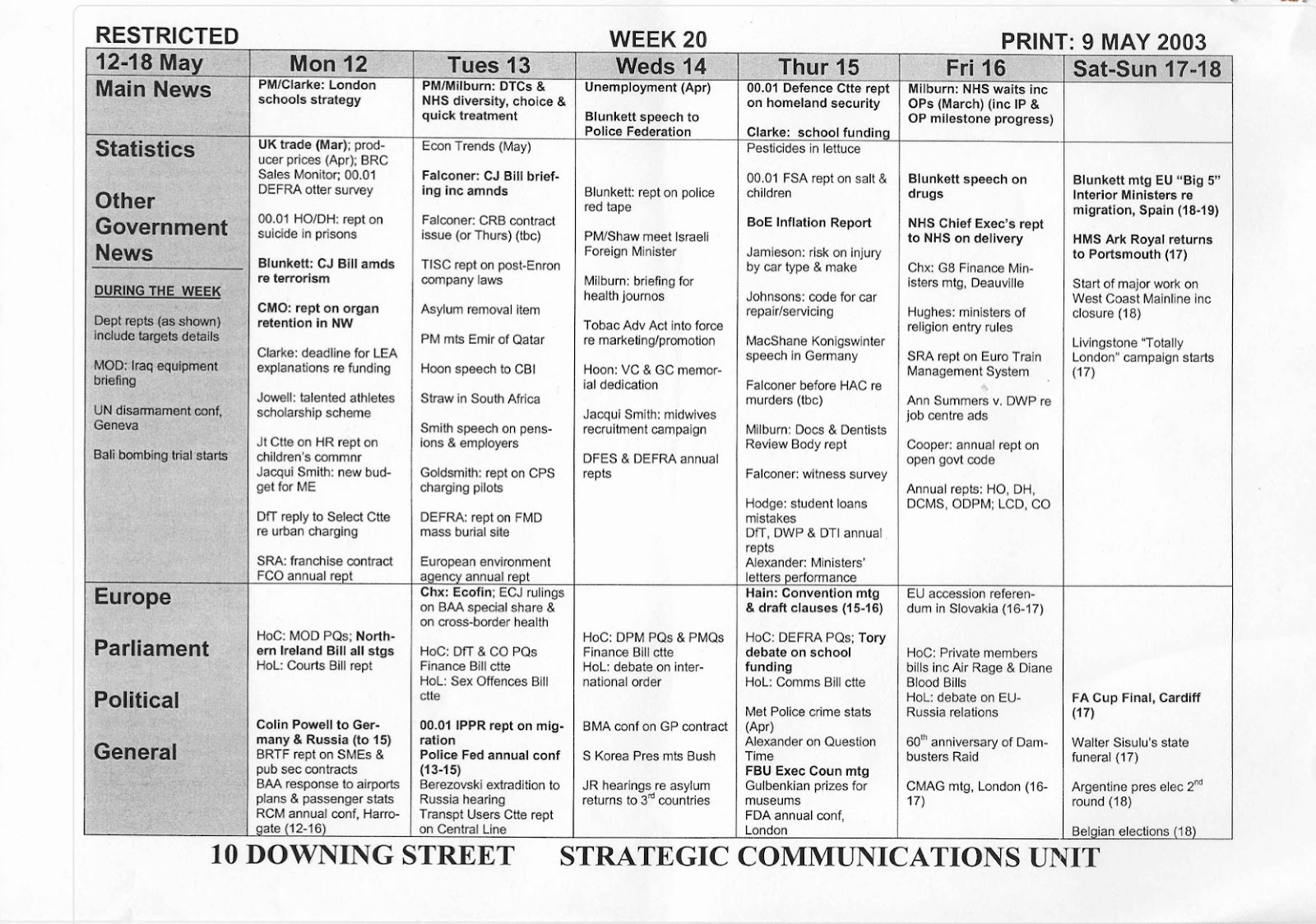

This is the grid that we used during the last Labour government. It hasn’t changed much since.

Its aim was simple but hard to achieve. To know what was going on in government and sequence it in some kind of order.

I’ll let you peruse this single week from 2003 at leisure. Just to explain. The main news at the top is the news that we hoped would dominate that day’s national newspaper and broadcast media. The second block contains all the other announcements that might get some billing - page 5 of the Times, sixth item on the BBC News at 10, a good airing in the specialist press, a possible question at Prime Minister’s Questions. Then the final list for each day is what else is going on in the world. In Europe. Internationally. In the real world. You’ll see, the Cup Final gets a mention on Saturday 17th. (Not at Wembley because it was being rebuilt, but at the Millennium stadium in Cardiff)

It gives some idea of the breadth of what goes on in government in a very average week: a talented athletes scholarship scheme, a schools’ strategy, a speech on drugs, an asylum removal story, a report on suicide in prisons. When journalists complain that the government doesn’t have a coherent story, the communications professional might retort: “you try to make sense out of that lot.” Twenty departments, five ministers in each, all spewing out random stuff.

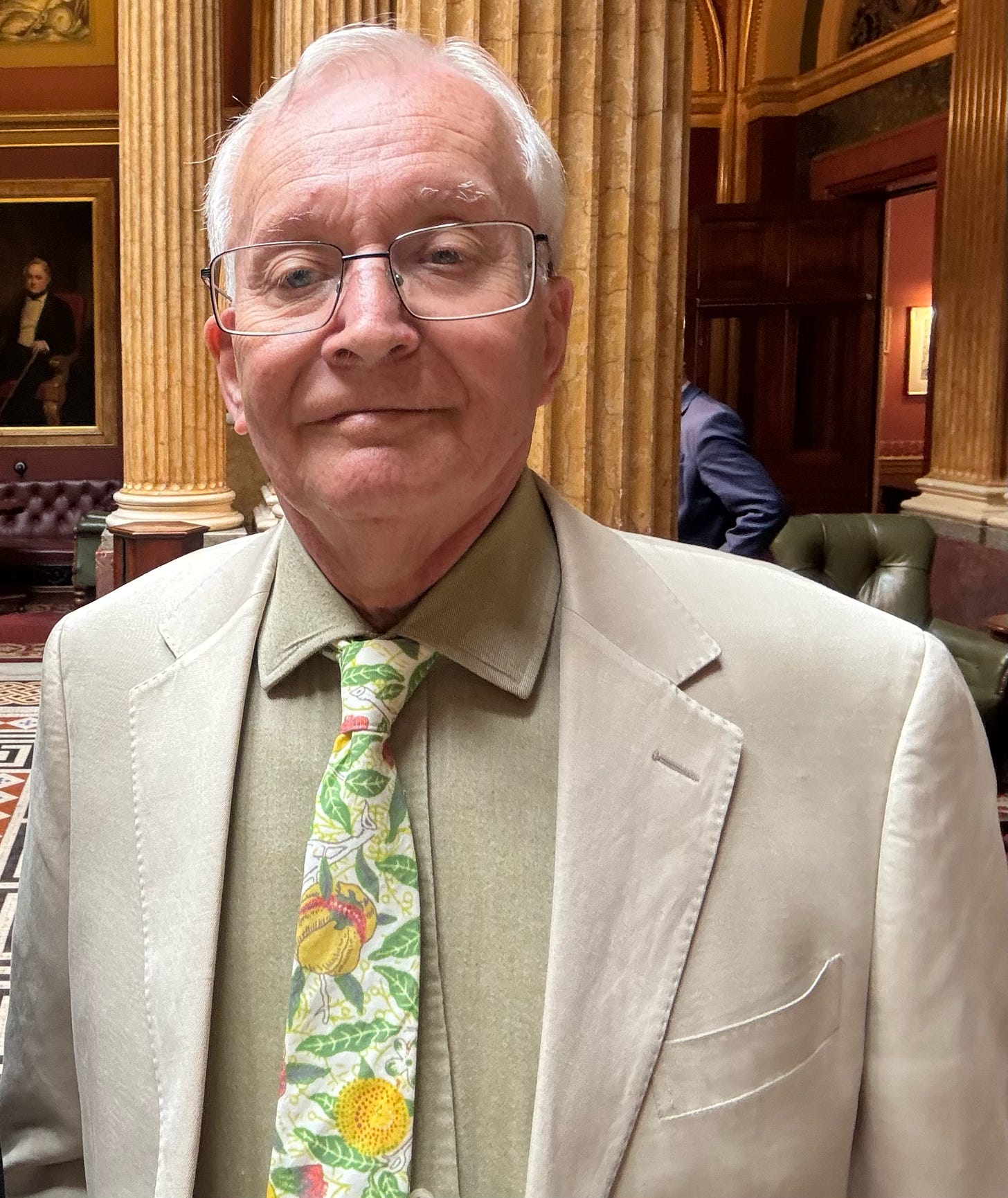

Paul Brown: Master of the Grid

But there was one man who, more than any other, tried to bring clarity to the chaos - Paul Brown.

Paul was a highly professional civil servant, who had spent time in the department of health working on Thatcher’s reforms and in the government Whip’s office. Known for having an eye for detail, he became the master of the grid - the single person who knew exactly what the government was planning to do.

Paul was unflappable and could even withstand the full force of a Gordon Brown or a John Prescott tirade when there was something on the grid they hated. The Paul Brown straight bat was something to behold.

When I caught up with him recently after twenty years, he hadn’t changed a bit, apart from swapping his trade-mark cardigan for a lightweight summer suit.

As I thrust the grid from 2003 into his hand, it became clear that, despite the passage of time, he still remembered the detail behind every one of those concise grid entries. He explained his process.

There were a lot of mistakes at first, you know. Mine, because I misinterpreted something, or a department, because they didn’t level with me. The information that came from departments was often pretty poor, and the press people, who were the people who basically briefed me, hadn’t got to page 75 of the white paper, and discovered that we weren’t going to have rubbish collections anymore. So things blew up unexpectedly. After a few years, we got to a position where departments knew they would keep themselves out of trouble, if they were on top of everything that was going on.

Paul eventually got each department to have a designated trusted person to lead on announcements and then he built them into a team. They enjoyed the status of coming to Number 10 for a Wednesday meeting where Paul would put them through their paces ensuring each of them knew exactly what the department was doing that week.

There were some fine judgement calls to be made each week. For example, Paul would have to weigh up how likely item 7 on Friday 16th of the above grid would be to take off - ‘Ann Summers v DWP re Job Centre ads.’ The actual story was:

In June 2003, Ann Summers won a legal challenge against the Department for Work and Pensions and JobCentre Plus after the High Court ruled that its ban on the company advertising staff vacancies in Jobcentres was unlawful and irrational. The ruling came after Ann Summers’ unsuccessful lobbying efforts failed to convince the government it was not part of the sex industry, leading to the company pursuing a judicial review of the policy, which Jobcentre Plus eventually conceded to.

Once he had got clarity on every item, he would produce a definitive copy of the grid, with 10 to 15 pages of detailed back up explanation, and it would go into the Prime Minister’s box on a Friday. It ensured the PM knew what the government was doing and also that he wasn’t blindsided at Prime Minister’s Questions.

The grid may seem an obvious creation to us now. But no one used them in those days. And when President Bush’s administration found out about the British grid, they thought it was a revelation and copied it. They wanted to ensure that in future the White House, State Department and Pentagon were not announcing stuff that either contradicted each other or clashed.

As Paul reflected:

Of course in the John Major years, it was utter chaos. Nobody knew what was going on, and the Prime Minister certainly didn’t. He would turn on the Today programme in the morning and hear that the government was doing something he didn’t know anything about.

For hostile journalists, Paul was the ‘burier of bad news’. That of course is not how he would have put it. But he did pride himself on amplifying the good stuff and playing down the bad.

You wouldn’t want a non-priority story getting in the way of one of our crown jewels. You don’t want to queer your own pitch. So that means you do tend to put the bad stories on a Friday. I used to take pride in how many of these I could get on the same day. You’ve got to be careful, of course, because journalists know what you were doing. All the specialist correspondents are looking out for PQ (Parliamentary Questions) replies and press notices and if they felt they’d been double crossed, they just covered it on another day of their choosing. Then we wouldn’t know when it was going to blow up. So it was actually better to be transparent about it.

Paul lived the detail to such an extent that:

After I retired I would have a recurring dream that I had got to Thursday, and I hadn’t got it sorted, and I knew I’d run out of time and I wouldn’t be able to get the stuff into the box for Friday.

Why the grid no longer works

As Paul confirmed to me, the grid was never very strategic. It was about sequencing existing government activity into a sane order and in particular making sure that the Prime Minister’s (and other senior Cabinet Ministers) big events were not subverted by other government activity. The grid was always Whitehall led - based on what departments offered up - it was never about developing key arguments, starting debates or commissioning new work.

I remember trying themed weeks to bring more coherence, for example, health week. But they never really worked. Paul confirms: “broadcasters had given you a big hit for one health announcement, so they very rarely let you have another big day in the same week.”

The grid was designed as a way of ensuring there was only one major story pumped out each day. It was based on the assumption that the main unit of currency was the perfectly formed policy announcement. A ‘one and done’ approach - you try to get one big hit for the policy and move on to the next subject. Yet, we now know that people have to hear something at least five times, from multiple sources, for it to stick.

While the main method of government communications remains the press release, we know that today, 70% of media is consumed in video form. And many get their news from social media.

The grid was not designed for a world in which anything can go viral and where false information, conspiracies, campaigns can take off rapidly to scupper a government policy.

Current Ministers complain that they can’t make the case on welfare, or recognition of the Palestinian state, or the new workers rights package, because Number 10 says there is no room on the grid. But in a world where citizens consume a huge variety of media, this makes no sense. If you are not out there on all the big arguments all the time, you lose. ID cards, which I talked about in my last Substack post, is a good current example. Irrespective of the grid, there should be a daily and on-going campaign to win the argument. At the moment the likelihood is that ID cards will only be given air time again in about a month at which point it will already be on the back foot.

The truth is that the grid, born in a less complicated media age, is now holding back the government from competing in the attention economy. It is too rigid. It is too easy to blow items off course by something more controversial.

In a previous post, I compiled a table showing the contrast between Trump communications and traditional communications. The grid, as currently designed, firmly anchors communications in the traditional column.

The playlist: an alternative to the grid

So perhaps after all these years, it’s time to overhaul the grid.

Of course, a calendar is needed for the big events. Everyone in government needs to know when the Budget is, or when there is a major Prime Ministerial intervention. The government still needs to prioritise a top broadcast story each day.

But after that, perhaps each department should be left to fight and win the battles that matter most.

We need to think of government activity more like a playlist than a grid. A playlist of the key arguments that need to be won in any given period. A playlist, because each of those arguments is targeted at key audiences. And like a music playlist, where you choose the tracks you want to listen to, a communications playlist allows you to tune into the arguments that most affect your life and your interests - on skills, AI or the NHS. And a greatest hits playlist is created for the overarching narrative of the government - the tune that you want everyone to hum, that is returned to again and again.

These playlists should effectively be campaigns with all the assets needed to win. Many of them can be run simultaneously. The implication of this approach is that the communications and media team at Number 10 could be grouped into two distinct operations. One team dealing with the day to day, the media requests and the reactive comms. The other, grouped into multi-disciplinary campaign teams - with marketing, digital media, videographers, copywriting, campaigning, local media, specialist media, polling and story development functions - with key players from the relevant departments and outside expertise where needed. For example, an NHS team with the Department of Health that is running an on-going campaign to communicate waiting list cuts over a three month period. Or a skills team developing, fleshing out, creating debates around the Prime Minster’s new target of two-thirds of young people going to university or undertaking a gold standard apprenticeship.

So, for example, this autumn there could be a campaigning playlist on each of the following:

Building new homes

Kickstarting growth

Tackling Illegal Immigration

Introducing ID cards

Unleashing a skills revolution

For each there needs to be a set of clear assets:

A strapline/slogan that everything fits under

A clear view of the audience that needs persuading

A week by week campaign grid including PM/Ministerial speeches, Op-Eds, talking points, digital media videos, events, podcasts, creator briefs for third party/influencer endorsements, and much more

A set of success criteria - measured not in how many articles appear in newspapers, but the real test - how much public opinion has shifted.

In my experience, the hardest thing to get right is the mindset shift required to see debates and arguments as the currency, not the policy nugget. Whitehall departments are used to offering up stories about money for something e.g. £10m for flowerpots in every community. There is a real skill (and it takes dedicated staff and ring-fenced time) in turning policy into emotionally resonant output - what you might call the LBC phone-in test. Is the announcement interesting enough to get people picking up the phone and voicing their opinion? In the attention economy, ‘worthy and dull’ is death.

Winning in the attention economy

One of the biggest problems for Labour in its first year has been the lack of strategic communications. The output has been too short term, too tactical and too reactive. The grid has strangled effective communication. A more agile and fluid process is now needed. I don’t expect the grid to be completely ditched. After all, it still gathers together key dates, events and big announcements that are happening inside and outside of government. But now is the time to run government communications as a playlist of the big arguments to be won, the big causes to be fought, and the big changes to be made. That is the best way of showing purpose, direction and momentum - and of convincing the public that the government is acting urgently each day on their behalf.

Great read, and a pleasure to meet you at Labour Conference.

Cracking piece. Fascinating about the history of the grid with a compelling arguments about how political communications need to adapt